Tyrannosaurus (pronounced /tɨˌrænəˈsɔːrəs/ or /taɪˌrænoʊˈsɔːrəs/, meaning 'tyrant lizard') is a genus of theropod dinosaur from North America. The famous species Tyrannosaurus rex ('rex' meaning 'king' in Latin), commonly abbreviated to T. rex (or incorrectly T-Rex), is a fixture in popular culture around the world, and is extensively used in scientific television and movies, such as documentaries and Jurassic Park, and in children's series such as The Land Before Time. Tyrannosaurus lived throughout what is now western North America, with a much wider range than other tyrannosaurids. Fossils of T. rex are found in a variety of rock formations dating to the last two million years of the Cretaceous Period, approximately 68 to 66 million years ago; it was among the last non-avian dinosaurs to exist prior to the Cretaceous–Tertiary extinction event.

Like other tyrannosaurids, Tyrannosaurus was a bipedal carnivore with a massive skull balanced by a long, heavy tail. Relative to the large and powerful hindlimbs, Tyrannosaurus forelimbs were small, though unusually powerful for their size, and bore two primary digits, along with a possible third vestigial digit. Although other theropods rivaled or exceeded T. rex in size]], it was the largest known tyrannosaurid and one of the largest known land predators, measuring up to 13.2 meters (43 ft) in length, up to 4 meters (13 ft.) tall at the hips, and up to 6.8 metric tonnes (7.5 short tons) in weight. By far the largest carnivore in its environment, T. rex may have been an apex predator, preying upon hadrosaurs and ceratopsians. Although some experts have suggested it was primarily a scavenger, this has been a highly controversial theory in recent years.

More than 30 specimens of T. rex have been identified, some of which are nearly complete skeletons. Soft tissue and proteins have been reported in at least one of these specimens. The abundance of fossil material has allowed significant research into many aspects of its biology, including life history and biomechanics. The feeding habits, physiology and potential speed of T. rex are a few subjects of debate. Its taxonomy is also controversial, with some scientists considering Tarbosaurus bataar from Asia to represent a second species of Tyrannosaurus and others maintaining Tarbosaurus as a separate genus. Several other genera of North American tyrannosaurids have also been synonymized with Tyrannosaurus.

Description[]

Size[]

Various specimens of Tyrannosaurus rex with a human for scale.

Life restoration of Tyrannosaurus rex

Tyrannosaurus rex was one of the largest land carnivores of all time; the largest complete specimen, FMNH PR2081 ("Sue"), measured 12.8 metres (42 ft) long, and was 4.0 metres (13 ft) tall at the hips.[1] Mass estimates have varied widely over the years, from more than 7.2 metric tons (7.9 short tons),[2] to less than 4.5 metric tons (5.0 short tons),[3][4] with most modern estimates ranging between 5.4 and 6.8 metric tons (6.0 and 7.5 short tons).[5][6][7][8]

Although Tyrannosaurus rex was larger than the well known Jurassic theropod Allosaurus, it was slightly smaller than Cretaceous carnivores Spinosaurus and Giganotosaurus.[9][10]

Skull[]

Profile view of a Tyrannosaurus skull (AMNH 5027).

T. rex's skull was capable of growing over five feet (1.5 meters) in length and was extremely robustly-built. The base was significantly wider than the snout, providing it with excellent binocular and stereoscopic vision, even greater than that of a human as studies suggest. Its mouth was broad compared to that of most other theropods and resembled a U-shape, increasing the amount of surface area it could chomp down on with a single bite. The skull retained several openings in it, known as "fenestra", that lightened the head and likely held soft tissue such as muscle or blood vessels, and the fenestra on top of its head may have served as a cooling mechanism, as seen in crocodiles.

Skull of T. rex type specimen located at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

Additionally, The T. rex's jaws averaged four feet (1.2 meters) in length and were very muscular, compensating for the animal's devastating biting strength. Analysis has shown that Tyrannosaurus was capable of opening its jaws up to approximately 63-80 degrees wide, maximum. The neck of the T. rex formed a natural S-shaped curve, similar to that of other theropods, but was relatively short, and would have been immensely robust in order to support its massive head. Tyrannosaur's often-ridiculed forelimbs were only around the size of an adult human's arms, but were anchored to powerful muscles (the T. rex's arms were capable of bench pressing 400 pounds each), and, unlike dinosaurs such as Carnotaurus and its relatives, were not vestigial and would have had some use in life, although the exact purpose for them is not entirely known. Unlike more basal theropods, Tyrannosaurus hands bore only two usable digits that were tipped with sharp claws, the third being undeveloped and was too small to have shown through the skin. In contrast to the forelimbs, the hind limbs were among the longest in proportion to body size of any theropod and incredibly muscular in order to support the animal's massive bulk. Its feet resembled those of terrestrial birds, with three longer toes that would have impacted the ground, and one vestigial hallux "dewclaw" that would have never touched the ground; each toe was tipped with massive slightly hoof-like claws.

The tail was long and heavy, occasionally containing over 40 vertebrae in order to balance the large head and torso. To compensate for its immense size, many bones throughout the skeleton were hollow (similar to birds and other theropods), reducing its weight without major loss of strength. The torso was wide and deep, resembling "barrel-chest". This body would have supported most of the animal's internal organs, with aid from the gastralia (belly ribs). Since Tyrannosaurus was a saurischian dinosaur, the pubis in the hips would have pointed forward and away from the backward-facing ischium.

The teeth of T. rex displayed some heterodonty (differences in shape). The teeth in the premaxilla (front upper jaw) were relatively small and closely packed, D-shaped in cross-section, possessed reinforcing ridges on the rear surface, were incisiform (their tips were chisel-like blades) and curved backwards, which all would have decreased the risk of the teeth breaking when animal bit and pulled. The remaining teeth were robust with a blunter shape compared to the dagger teeth of basal theropods, more widely spaced and also possessed reinforcing roots. The teeth in the middle of the maxilla were the largest in its jaws; the biggest Tyrannosaurus tooth discovered currently was recorded as measuring 30.5 cm (12 inches) in length, including the root, making it the largest tooth of any carnivorous dinosaur and easily one of the most immense teeth in the animal kingdom.

Classification[]

T. rex head reconstruction at the Oxford University Museum of Natural History.

Tyrannosaurus is the type genus of the superfamily Tyrannosauroidea, the family Tyrannosauridae, and the subfamily Tyrannosaurinae; in other words it is the standard by which paleontologists decide whether to include other species in the same group. Other members of the tyrannosaurine subfamily include the North American Daspletosaurus and the Asian Tarbosaurus,[11][12] both of which have occasionally been synonymized with Tyrannosaurus.[13] Tyrannosaurids were once commonly thought to be descendants of earlier large theropods such as megalosaurs and carnosaurs, although more recently they were reclassified with the generally smaller coelurosaurs.[14]

Paleobiology[]

Life history[]

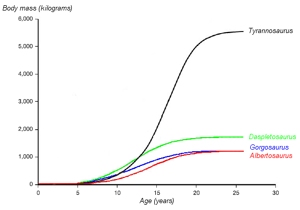

A graph showing the hypothesized growth curves (body mass versus age) of four tyrannosaurids. Tyrannosaurus rex is drawn in black. Based on Erickson et al. 2004.

The identification of several specimens as juvenile Tyrannosaurus rex has allowed scientists to document ontogenetic changes in the species, estimate the lifespan, and determine how quickly the animals would have grown. The smallest known individual (LACM 28471, the "Jordan theropod") is estimated to have weighed only 29.9 kg (66 lb), while the largest, such as FMNH PR2081 ("Sue") most likely weighed over 5400 kg (6 short tons). Histologic analysis of T. rex bones showed LACM 28471 had aged only 2 years when it died, while "Sue" was 28 years old, an age which may have been close to the maximum for the species.[8]

Posture[]

Outdated reconstruction (by Charles R. Knight), showing 'tripod' pose. |

Replica at Senckenberg Museum, showing modern view of posture. |

Like many bipedal dinosaurs, Tyrannosaurus rex was historically depicted as a 'living tripod', with the body at 45 degrees or less from the vertical and the tail dragging along the ground, similar to a kangaroo. This concept dates from Joseph Leidy's 1865 reconstruction of Hadrosaurus, the first to depict a dinosaur in a bipedal posture.[15] Henry Fairfield Osborn, former president of the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) in New York City, who believed the creature stood upright, further reinforced the notion after unveiling the first complete T. rex skeleton in 1915. It stood in this upright pose for nearly a century, until it was dismantled in 1992.[16] By 1970, scientists realized this pose was incorrect and could not have been maintained by a living animal, as it would have resulted in the dislocation or weakening of several joints, including the hips and the articulation between the head and the spinal column.[17]

History[]

Skeletal restoration by William D. Matthew from 1905, which was the first reconstruction of Tyrannosaurus rex ever published[18]

Henry Fairfield Osborn, president of the American Museum of Natural History, named Tyrannosaurus rex in 1905. The generic name is derived from the Greek words τυραννος (tyrannos, meaning "tyrant") and σαυρος (sauros, meaning "lizard"). Osborn used the Latin word rex, meaning "king", for the specific name. The full binomial therefore translates to "tyrant lizard king," emphasizing the animal's size and perceived dominance over other species of the time.[19]

Sue[]

"Sue" the Tyrannosaurus, Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, showing the forelimbs. The 'wishbone' is between the forelimbs.

Sue Hendrickson, amateur paleontologist, discovered the most complete (more than 90%) and, until 2001, the largest, Tyrannosaurus fossil skeleton known in the Hell Creek Formation near Faith, South Dakota, on 12 August 1990. This Tyrannosaurus, nicknamed "Sue" in her honor, was the object of a legal battle over its ownership. In 1997 this was settled in favor of Maurice Williams, the original land owner, and the fossil collection was sold at auction for USD 7.6 million, making it the most expensive dinosaur skeleton to date. It has now been reassembled and is currently exhibited at the Field Museum of Natural History. A study of this specimen's fossilized bones showed that "Sue" reached full size at age 19 and died at age 28, the longest any tyrannosaur is known to have lived.[20] The "Sue" specimen apparently died from a massive bite to the head, which could only have been inflicted by another tyrannosaur.[21]

Cultural Influence[]

Since it was first described in 1905, Tyrannosaurus rex has become the most widely recognized dinosaur in popular culture. It is the only dinosaur which is routinely referred to by its full scientific name (Tyrannosaurus rex) among the general public, and the scientific abbreviation T. rex has also come into wide usage (commonly misspelled "T-Rex").[22] Robert T. Bakker notes this in The Dinosaur Heresies and explains that a name like "Tyrannosaurus rex is just irresistible to the tongue."[4]

General Impact[]

Tyrannosaurus rex is unique among dinosaurs in its place in modern culture; paleontologist Robert Bakker has called it "the most popular dinosaur among people of all ages, all cultures, and all nationalities".[23] From the beginning, it was embraced by the public. Henry Fairfield Osborn billed it the greatest hunter to have ever walked the earth. He stated in 1905,[24]

In 1942, Charles R. Knight painted a mural incorporating Tyrannosaurus facing a Triceratops in the Field Museum of Natural History for the National Geographic Society, establishing the two dinosaurs as enemies in popular thought;[25] paleontologist Phil Currie cites this mural as one of his inspirations to study dinosaurs.[24] Bakker said of the imagined rivalry between Tyrannosaurus and Triceratops, "No matchup between predator and prey has ever been more dramatic. It’s somehow fitting that those two massive antagonists lived out their co-evolutionary belligerence through the very last days of the very last epoch of the Age of Dinosaurs."[25]

JPInstitute.com Description[]

Probably the most famous of all dinosaurs, T. rex was probably the fiercest meat eater that ever lived. At more than 45 feet in length, it was huge and had the most powerful head of any dinosaur. It also had the biggest teeth of any dinosaur - teeth that were not only sharp and cutting edged, but also thick and strong, capable of crushing bones.

After many millions of years of evolution, nature arrived at T. rex, an almost perfect killing machine. It had large feet to help it run quickly through the swampy environment in which it lived. Although it had very short arms, it didn't need its arms to be an effective and efficient killer. It had enormous strength in its jaws; it could bite right through the frill of a Triceratops or into the back of a hadrosaur. In fact, the only thing that a T. rex had to fear was another T. rex. Most of the scars and wounds found on fossil bones of these great creatures seem to come from others of its kind.

T. rex is very well known, with more than 30 individual specimens having been found. Less than half of these had any significant amount of the fossil, but it still gives us a very good picture of these creatures. The most famous of the fossils of this creature is "Sue" which is now on display at the Field Museum in Chicago. Sue is about 42 feet long; her largest tooth is almost 13 inches.

T. rex is a good example of how our thinking about dinosaurs has changed based on how much we have learned. Back in 1915 when the first skeleton was mounted, most people thought it was a slow beast that dragged its tail along the ground. This view was partially because it would have been very expensive to mount it any other way, and scientists weren't sure how it looked in life. Now, scientists are confident that they understand how T. rex and other dinosaurs looked and lived. T. rex probably walked and ran with its back and tail parallel to the ground, its massive legs and hips a fulcrum for its body. It was an active beast, and recent evidence strongly suggests it was warm blooded.

It has recently been debated as to whether T. rex was strictly a hunter or strictly a scavenger. Their is evidence to both sides of this debate and most scientists believe that T. rex was both an effective hunter and an opportunistic scavenger.

Dinosaur Field Guide Description[]

Tyrannosaurus ("tyrant lizard") is one of the most well-known of all dinosaurs, It is no longer considered the largest of the theropods (see Giganotosaurus), but it is certainly one of the fiercest and most powerful. Tyrannosaurus is the last and largest of the tyrannosaurs, or tyrant dinosaurs. Like other tyrant dinosaurs, Tyrannosaurus has very short arms with only two fingers. Although these were probably useless while hunting, its jaws were not; Tyrannosaurus has an enormous skull armed with teeth the size of bananas! Unlike the teeth of most meat-eaters, tyrant dinosaur teeth are very thick and capable of crushing bones. The skull and neck bones show that T. rex had the largest neck muscles of any meat-eating dinosaur. It probably used its strong neck to twist and pull off big chunks of meat that it grasped with its jaws. Tyrannosaurus could bite with extremely strong force one fossilized skeleton shows that it crushed and swallowed the bones of a smaller plant-eating dinosaur. Most dinosaurs, in general, had eyes facing sideways, which allowed them to see all around themselves. The eyes of Tyrannosaurus, though, faced forward so it could focus better on a single object and tell precisely how far away it was.

This would be very useful for a hunter-especially one that had to fight Triceratops, one of the most dangerous plant-eating dinosaurs of all. The legs of the tyrant dinosaurs were long and slender for their size, allowing them to chase down the horned dinosaurs and duckbills that were the most common plant-eaters of their time. In fact, a specimen of the duckbill Edmontosaurus shows a bite mark taken out of its tail that matches the bite of Tyrannosaurus. Because this bite was healed, we know that the Edmontosaurus managed to get away from its attacker! Although some people think that the female Tyrannosaurus was larger than the male, there is no real evidence for this. Indeed, paleontologists do not yet know how to tell a male Tyrannosaurus from a female from just the skeleton. It is known, though, that Tyrannosaurus led a rough life. Some specimens show many broken bones that had healed over.[26]

Fun Facts[]

A fossilized T. rex dropping was found in Saskatchewan, Canada, in 1995. It was filled with the broken and digested bones of a plant-eating dinosaur. The dropping was the size of a loaf of bread!

Trivia[]

Tyrannosaurus had the biggest brain of any dinosaur known.

Gallery[]

Fact Card[]

Download a flash card to cut out and quiz your friends: File:Dftyran.pdf

Related Articles[]

Appearance in Jurassic Park and other media[]

Jurassic Park[]

Tyrannosaurus rex has arguably made its most iconic role in the movie Jurassic Park (1993) and all of its sequels such as The Lost World: Jurassic Park (1997), Jurassic Park III (2001), Jurassic World (2015), Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom (2018), and Jurassic World: Dominion (2022) as well as both of the original novels by Michael Crichton. It has acted as a powerful carnivore that often saves the main protagonists (most notably near the end of the movie) and occasionally fights another carnivore that is typically portrayed as a villain (examples include Giganotosaurus and Indominus rex). The most notable Tyrannosaurus from the Jurassic series is Rexy, appearing since the first installment all the way to Dominion, with the only movies she wasn't featured in being The Lost World and Jurassic Park III. Other notable Tyrannosaurus characters are Buck, Doe, and a baby Tyrannosaurus all from The Lost World, and Bull, a younger adult from Jurassic Park 3 most popular for dying against the Spinosaurus. There are also two Tyrannosaurus recurring characters in the Netflix tie-in show Camp Cretaceous, a mother-daughter duo known as Big Eatie and Little Eatie.

| Read more Tyrannosaurus on Jurassic Park Wiki |

The Land Before Time[]

In both the films and television series, Tyrannosaurus plays an important role in sequences involving predators, similarly to the T. rex in Jurassic Park. There are exceptions to T. rex being portrayed in antagonistic lights, however; the character Chomper is a Tyrannosaurus who is a member of the Prehistoric Pals.

As is the case for all carnivorous dinosaurs in the series, though some others have more specific terms, the herbivorous characters simply refer to Tyrannosaurus as "sharpteeth".

| Read more Tyrannosaurus on Land Before Time Wiki |

We're Back! A Dinosaur's Story[]

Links[]

https://web.archive.org/web/20080517023754/http://kids.yahoo.com/dinosaurs/49--Tyrannosaurus

References[]

- ↑ Sue's vital statistics Sue at the Field Museum. Field Museum of Natural History.

- ↑ Henderson, DM, 1999. Estimating the masses and centers of mass of extinct animals by 3-D mathematical slicing, from the Journal of Paleobiology, vol. 25, issue 1, pp. 88–106 [1].

- ↑ Anderson, JF and Hall-Martin AJ, Russell, Dale A. 1985. Long bone circumference and weight in mammals, birds and dinosaurs, from the Journal of Zoology, vol. 207, issue 1, pp. 53–61.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Bakker, Robert T., 1986. The Dinosaur Heresies. New York, Kensington Publishing, ISBN 0-688-04287-2

- ↑ Farlow, James O., Smith MB, & Robinson, JM, 1995. Body mass, bone "strength indicator", and cursorial potential of Tyrannosaurus rex, from the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, vol. 15, issue 4, pp. 713–725. [2]

- ↑ Seebacher, Frank. 2001. A new method to calculate allometric length-mass relationships of dinosaurs, from the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, vol. 21, issue 1, pp. 51–60.

- ↑ Christiansen, Per & Fariña, Richard A., 2004. Mass prediction in theropod dinosaurs, from the Journal of Historical Biology, vol. 16, issues 2-4, pp. 85–92.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Erickson, Gregory M., Makovicky, Peter J.; Currie, Philip J.; Norell, Mark A.; Yerby, Scott A.; & Brochu, Christopher A. 2004. Gigantism and comparative life-history parameters of tyrannosaurid dinosaurs, from the Journal of Nature, vol. 430, issue 7001, pp. 772–775. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "ericksonetal2004" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ dal Sasso, Cristiano and Maganuco, Simone; Buffetaut, Eric; & Mendez, Marcos A. 2005. New information on the skull of the enigmatic theropod Spinosaurus, with remarks on its sizes and affinities, from the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology vol. 25, issue 4, pp. 888–896. [3]

- ↑ Calvo, Jorge O., and Rodolfo Coria, 1998, December. New specimen of Giganotosaurus carolinii (Coria & Salgado, 1995), supports it as the as the largest theropod ever found, from the Journal of Gaia Revista de Geociências, vol. 15, pp. 117–122. [4]

- ↑ Philip J. Currie, Jørn H. Hurum and Karol Sabath. 2003. Skull structure and evolution in tyrannosaurid dinosaurs, from the Journal of Acta Palaeontologica Polonica, vol. 48, issue 2. pp. 227–234. [5]

- ↑ David B. Weishampel, Peter Dodson and Halszka Osmólska, The dinosauria. University of California Press, in Berkeley, 2004. pp. 111–136, ISBN 0-520-24209-2 Chapter: Tyrannosauroidea, Thomas R., Jr. Holtz.

- ↑ Paul, Gregory S. Predatory dinosaurs of the world: a complete illustrated guide. Simon and Schuster, in New York. 1988. ISBN 0-671-61946-2

- ↑ Holtz, Thomas R., 1994. The Phylogenetic Position of the Tyrannosauridae: Implications for Theropod Systematics, from the Journal of Palaeontology, vol. 68, issue 5, pp. 1100–1117 http://www.jstor.org/pss/1306180

- ↑ Leidy, J, 1865. Memoir on the extinct reptiles of the Cretaceous formations of the United States, from the journal of Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge, vol. 14, pp. 1–135.

- ↑ Tyrannosaurus, from the American Museum of Natural History. Retrieved on January 25th, 2009.

- ↑ Newman, BH, 1970. "Stance and gait in the flesh-eating Tyrannosaurus", from the Biological Journal of the Linnean Society, vol. 2, pp. 119–123.

- ↑ The First Tyrannosaurus Skeleton, 1905, published by Linda Hall, of the Library of Science, Engineering and Technology. [6].

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedosborn1905 - ↑ Stokstad, E.,"Bone Study Shows T. rex Bulked Up With Massive Growth Spurt", from the Science journal, (13 August 2004), vol. 305, issue 5686, pp. 930–931. [7].

- ↑ Lessons From A Tyrannosaur: The Ambassadorial Role Of Paleontology, by Brochui, C.A., from the Palaios journal. Vol. 18, issue 6, (December, 2003). [8]. Page: 475.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedbrochu2003 - ↑ Bakker, Robert. Edited by Fiffer, S. Tyrannosaurus Sue (2000). Publisher: W. H. Freeman & Company, in New York ISBN 0-7167-4017-6 pp. xi-xiv Chapter: Prologue.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 John "Jack" Horner and Don "Dino" Lessem, The Complete T. Rex (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1993), pages 58-62

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Bakker, R.T. 1986. The Dinosaur Heresies. New York: Kensington Publishing, p. 240. On that page, Bakker has his own T. rex/Triceratops fight.

- ↑